Pressure Measurement

Understanding Industrial Pressure Measurement: Key Concepts and Applications

1. Pressure Concept

Pressure is a basic variable in the design, construction and maintenance of industrial processes.

Pressure measurement is the primary variable for a wide range of process measurements, for example:

- Flow rate (measuring pressure loss through a restriction).

- Liquid level (measuring the pressure created by a vertical column of liquid).

- Density of the liquid (measuring the pressure difference across a defined liquid height).

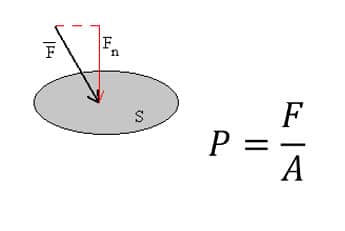

Pressure is defined as the ratio of the normal component of the force on a surface to the area of that surface.

The knife will cut better the sharper it is, because the force exerted is concentrated on a smaller area.

The skier does not sink into the snow because the force is spread over a larger area.

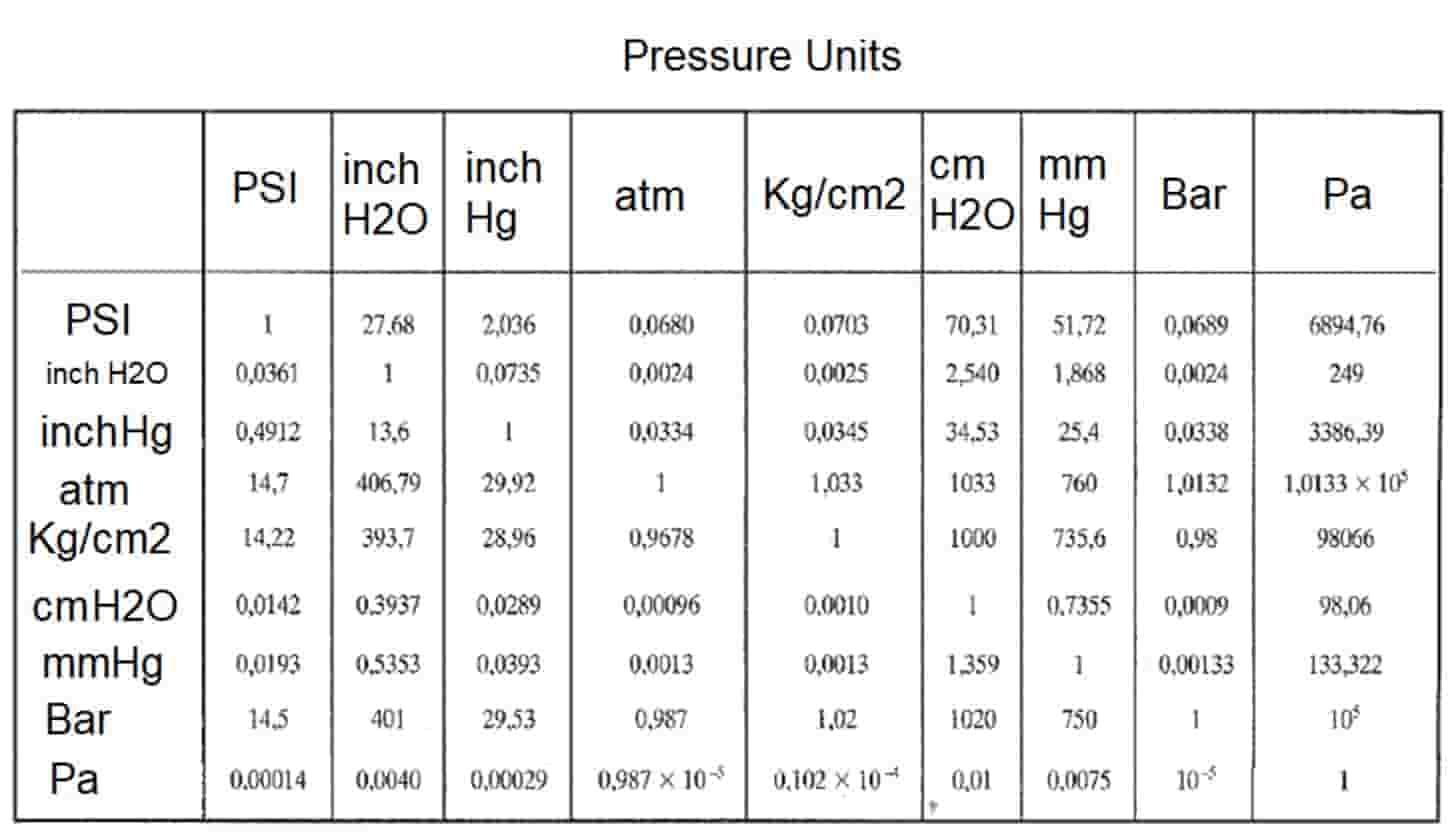

1.1 Pressure - Unit Conversion Table

2. Fluid Concept

In general terms matter can be classified into solids and fluids. The word fluid describes something that can flow (this includes liquids and gases).

The distinction between liquids and gases is not well defined, by varying the environmental conditions it is possible to transform a liquid into a gas and vice versa.

A fluid can be defined as a substance that does not resist, in a permanent way, the deformation caused by a force, therefore it changes its shape (be water my friend).

2.1 Compressibility

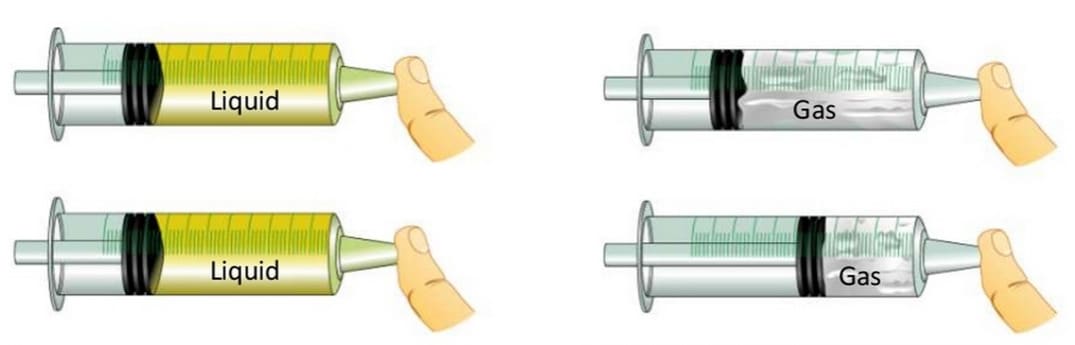

We will distinguish 2 types of fluids:

- Incompressible: They are little affected by pressure changes. Their density is constant.

- Most liquids are incompressible.

- Gases can be considered incompressible when the pressure variation is small with respect to the absolute pressure.

- Compressible: They are affected by pressure by varying their density. Most of the gases are compressible.

2.1.1 Incompressible Fluids

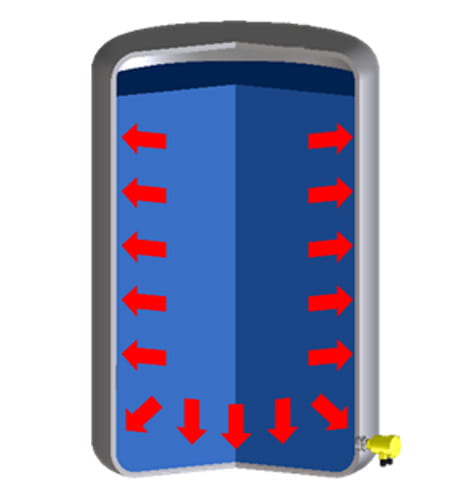

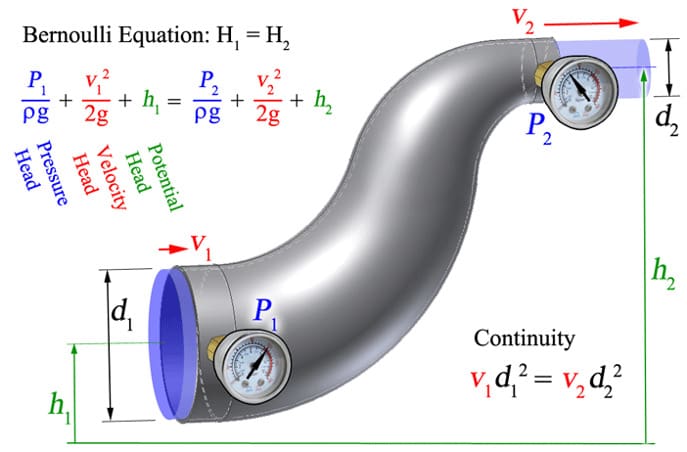

According to Bernoulli, we can decompose the pressure of an incompressible fluid into 2 components:

- Static pressure:

- All points at the same depth will be subjected to the same pressure, regardless of the shape of the vessel in which the liquid is contained.

- Dynamic pressure:

According to Euler's continuity equation (mass balance):

2.1.2 Compressible Fluids

As we know gases are highly compressible fluids.

From a mechanical point of view, the fundamental difference between liquids and gases is that the latter can be compressed. Their volume, therefore, is not constant and consequently neither is their density.

Considering the fundamental role of this physical quantity in fluid statics, it is understandable that the equilibrium of gases must be considered separately from that of liquids.

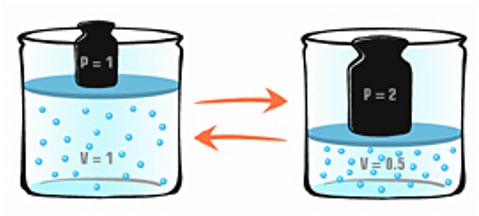

Boyle's Law

“The volume of the gas contained in a container is reduced if the pressure is increased.”

The theoretical study of the flow of a gaseous fluid is beyond the scope of this presentation, as a note we indicate that the propagation of pressure within a compressible fluid is performed at speeds close to the speed of sound.

3. Pressure Types

You can find more detailed information about Pressure Types in ./whats-the-difference-between-absolute-gauge-and-differential-pressure.html.

3.1 Atmospheric Pressure

It is caused by the weight of the atmosphere. It depends on climatic changes, the reference value is taken at sea level which is equal to 1013 mbar or 760 mmHg.

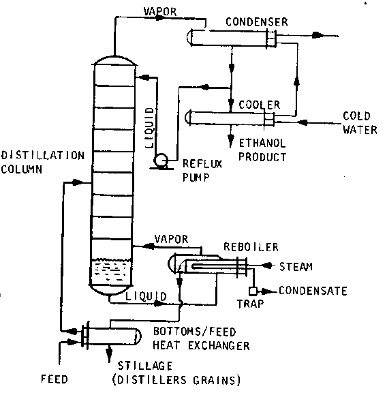

3.2 Differential Pressure

It is defined as the difference between two pressures, also known as dP, pressure drop, etc....

APPLICATIONS:

- Level measurement in closed tanks

- Density Measurement

- Flow Measurement

- Interface Level Measurement

- Distillation Col. monitoring Flooding

- Filter monitoring

- Pump and valve monitoring

- Fire System Monitoring - Sprinklers

- Process Feed Pressure Monitoring

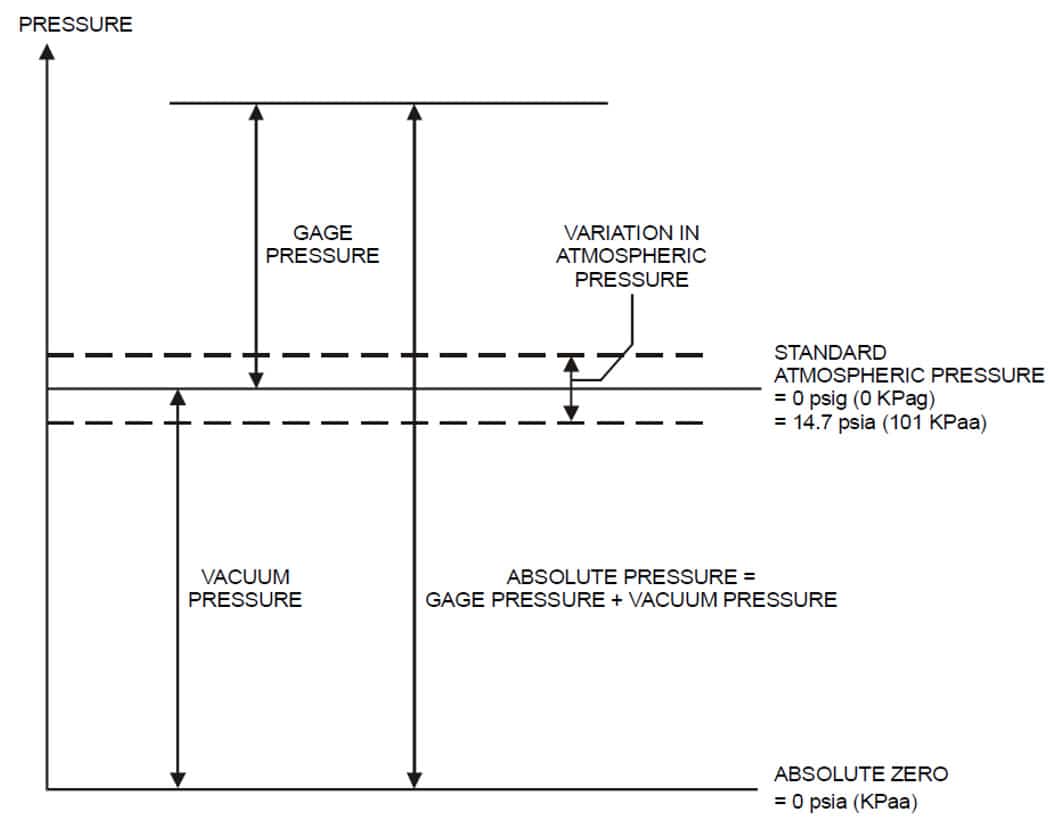

3.3 Absolute Pressure

It is defined as the pressure referred to absolute zero pressure. It is distinguished by the subscript abs. Another way of defining it is by adding the atmospheric pressure to the relative / gauge pressure indicated by the measurement.

APPLICATIONS:

- Applications where high accuracy in vacuum measurement is required

- Low pressure or vacuum applications where it is necessary for pressure control to measure the influence of atmospheric pressure.

- Low pressure measurement in vacuum distillation columns

- Vacuum reactors

- Control of leaks in tanks and circuits

3.4 Relative Pressure

It is determined by an element that measures the difference between absolute and atmospheric pressure.

It is distinguished by the subscript reg or g.

They make up 95% of the types of meters installed in the chemical industry. It can be positive (P1>Patm) or negative also known as empty (P1<Patm).

APPLICATIONS:

- Level measurement in atmospheric tanks.

- Pressure measurement in circuits and pressure equipment where the working pressure suffers variations greater than those caused by variations due to the atmosphere.

- Air conditioning and control of air and corrosive gases - Clean rooms.

4. Pressure Gauges

4.1 PI - Indicators

4.1.1 Pressure Gauges

Pressure gauges are primary standards of most national standards bureaus.

The main advantages of these instruments are their high accuracy, low cost and simplicity, minimum span with inclined ranges from 0 to 2.5mm H2O; maximum span is 4bar.

The accuracy is 0.2 mmH2O for vertical and 0.05 mmH2O for inclined.

The major limitations are possible rupture and problems related to the contained fluid.

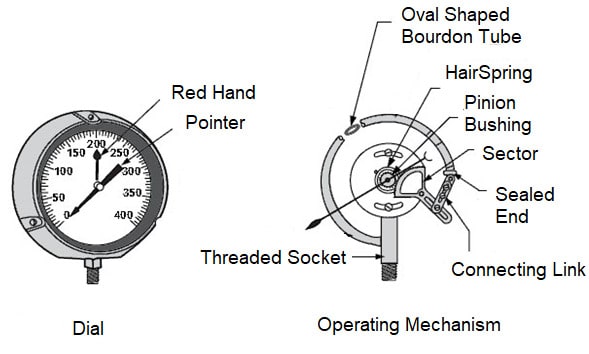

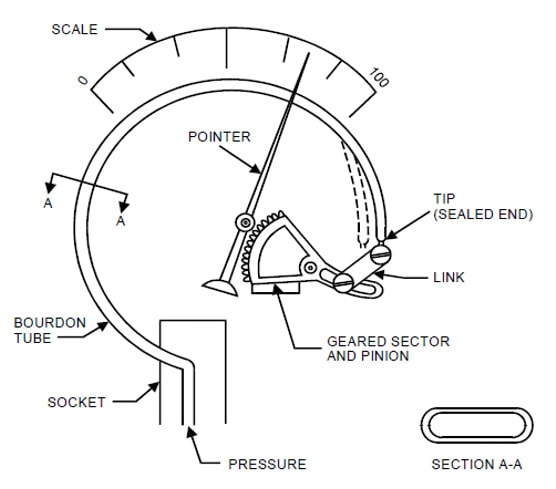

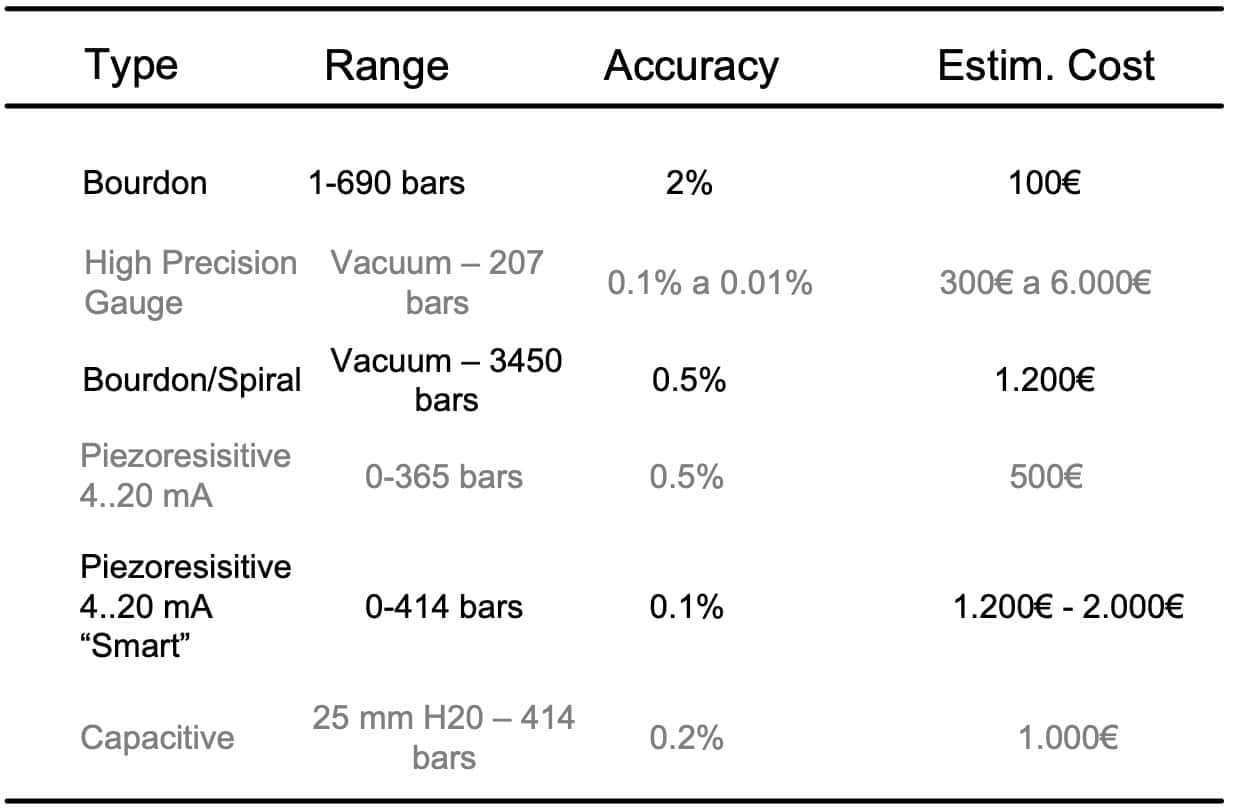

4.1.2 Bourdon Tubes

In 1852 E.Bourdon patented a curved tube which, when held and pressurized at its open end, produces a movement at its closed end.

Bourdon tubes are used to detect high pressures, not good at low pressures or vacuum, span from 1bar to 6900bar.

Their accuracy varies from 0.25 to 5% of span. They are used as PI standard in many process industries.

The main advantages are low cost, easy replacement.

4.2 PT - Transmitters

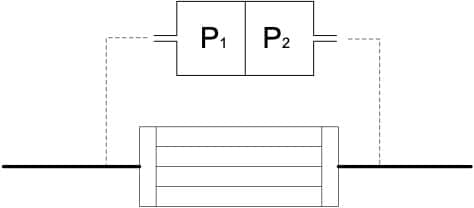

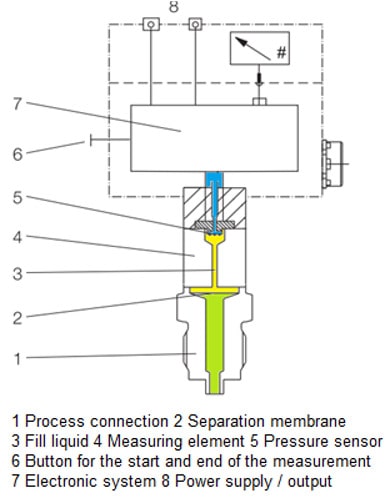

These instruments are composed of two functional units:

- Primary Unit: The pressure transducer (primary unit) consists of the interface to the process, the sensor and the primary electronics.

-

The primary electronics converts these variations into a digital signal that feeds a microcontroller. This performs a linearization of the primary output, compensating for sensor non-linearity, static pressure and temperature changes.

-

The measured values and sensor parameters are transferred to the subunit, where the communications card is located. The output data value is converted to a 4-20 mA signal.

- Secondary Unit: It consists of the rest of the electronics, the terminal block and the enclosure.

4.2.1 Piezo-Resistive

It is the most popular pressure gauge.

It consists of the diffusion of resistive elements inside a single silicon chip, acting as a diaphragm.

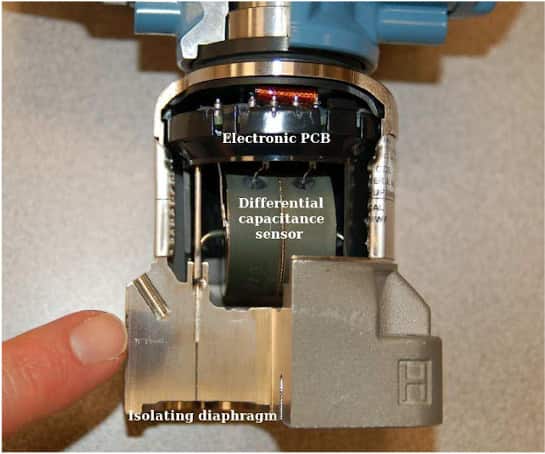

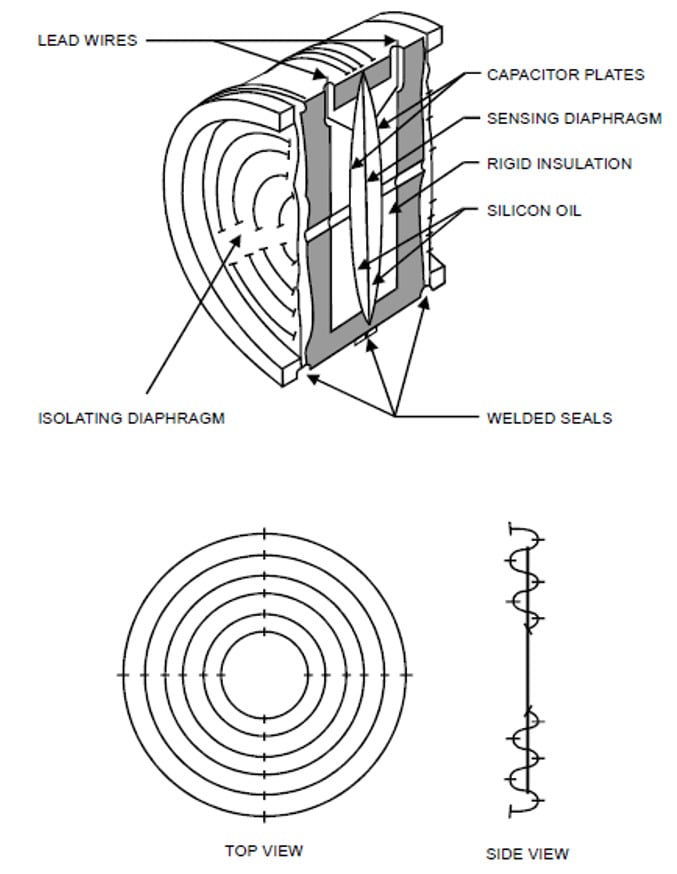

4.2.2 Capacitive

A capacitor consists of two parallel conducting plates separated by a small gap. Pressure displaces one of the plates that acts as a diaphragm.

4.3 Selection Criteria

4.4 Process Connection

5. Pressure Suppliers List

- ABB Instrumentation (www.abb.com/us/instrumentation)

- Barton Instruments (www.barton-instruments.com)

- Brooks Instrument (www.brooksinstrument.com)

- Dresser Instrument (www.dresserinstruments.com)

- Endress + Hauser Inc. (www.us.endress.com)

- Fisher controls (www.fisher.com)

- Foxboro/Invensys (www.foxboro.com)

- Honeywell (www.iac.honeywell.com)

- Marsh Bellofram (marshbellofram.com)

- Moore Industries (www.miinet.com)

- Rosemount/Emerson (www.rosemount.com)

- Siemens (www.sea.siemens.com)

- United Electric (www.ueonline.com)

- Youkogawa Corp. of America (www.yca.com)

- Yokogawa Electric Corp. (www.yokogawa.com)